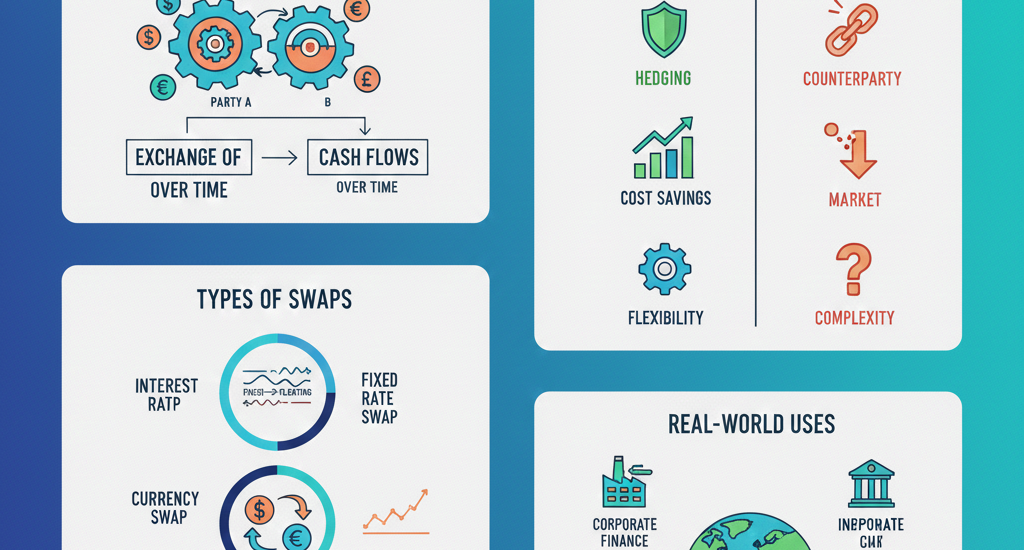

In the world of finance, companies, banks, and investors constantly look for ways to manage risk, stabilize costs, and improve financial performance. One of the most useful tools created for this purpose is the swap. Although the term may sound complex, a swap is simply a contract in which two parties agree to exchange cash flows over a specific period. These exchanges are usually based on interest rates, currencies, commodities, or even the performance of certain assets. Swaps have grown into one of the most important financial instruments in global markets because they allow institutions to handle risks without changing the underlying assets or debt on their balance sheets.

At its core, a swap involves two streams of payments. One stream might be fixed, while the other is variable or floating, depending on some economic benchmark such as an interest rate or a currency exchange rate. The key thing to understand is that swaps do not involve exchanging the actual principal amount. Instead, both parties agree on a “notional principal,” which is used purely to calculate the cash flows they will swap. Since the principal itself never changes hands, swaps can be executed efficiently without disrupting a company’s finance structure.

Swaps are typically traded privately in what’s known as the over-the-counter (OTC) market. This means they are not bought and sold on centralized exchanges like stocks or futures. Instead, they are negotiated directly between two institutions, usually with the help of banks or specialist dealers. The OTC nature of swaps allows for customization—contracts can be tailored to suit the exact needs of the parties involved. However, this also brings counterparty risk, which is the possibility that one party may not be able to meet its payment obligations. After the financial crisis of 2008, regulations increased oversight on swap trading, but most swaps are still customized OTC contracts.

One of the most common forms is the interest rate swap. In an interest rate swap, two parties exchange interest payments on a certain notional amount. Typically, one party pays a fixed rate, while the other pays a floating rate linked to a benchmark such as LIBOR or SOFR. Think of a company with a loan that has a floating interest rate. If interest rates rise, so will their payments, making budgeting difficult. To stabilize costs, the company might enter into an interest rate swap where it pays a fixed rate to a counterparty and receives a floating rate in return. This exchange essentially converts its variable-rate debt into fixed debt without modifying the original loan. Interest rate swaps are widely used because they help companies protect themselves against unpredictable rate movements.

Another important type is the currency swap. These swaps involve exchanging cash flows in different currencies. Unlike interest rate swaps, currency swaps sometimes require exchanging principal amounts at the beginning and end of the contract, although not always. Currency swaps are commonly used by companies that operate internationally and need to manage exchange-rate risks. Suppose a U.S. company needs euros for a European investment, while a European company needs U.S. dollars for operations in the United States. A currency swap allows both companies to obtain the currency they need directly from each other, often at better terms than banks can offer. They also help avoid the instability that comes with fluctuating exchange rates.

Beyond interest rates and currencies, the financial industry has developed a variety of specialized swaps. Commodity swaps involve exchanging cash flows tied to commodity prices such as oil, natural gas, or metals. These are useful for businesses exposed to volatile commodity markets. For example, an airline worried about rising fuel prices can use a commodity swap to lock in fuel costs for future months. Equity swaps and total return swaps link cash flows to the performance of equity indices or individual stocks. These instruments allow investors to gain exposure to assets without actually owning them. Hedge funds and investment banks frequently use these swaps to manage investment exposure, reduce taxes, or bypass restrictions on direct ownership.

One of the most well-known forms of swap is the credit default swap (CDS). A CDS functions like insurance on a financial asset such as a bond. The buyer of the CDS makes periodic payments to the seller. In return, the seller promises to compensate the buyer if the underlying bond issuer defaults. Before the financial crisis, CDS contracts were widely used by institutions seeking protection from credit risk. However, misuse and lack of regulation contributed to systemic issues in 2008. Even so, credit default swaps remain a significant part of the financial landscape, now with stronger regulatory oversight.

Swaps offer major advantages. They allow companies to manage interest rate risk, currency exposure, and commodity price volatility without restructuring their debt or engaging in complicated asset transactions. Swaps also tend to be more flexible than traditional financial products. Since they are negotiated directly between two parties, almost any specification—payment schedule, notional amount, rate benchmarks—can be tailored to fit unique business needs.

However, swaps are not risk-free. Because they are long-term agreements, changes in market conditions can lead to unexpected costs for one party. For example, if a company agrees to pay a fixed rate in an interest rate swap and market rates fall, it may end up paying more than necessary. There is also counterparty risk: if one party defaults, the other may lose expected payments. This makes it important to choose financially strong partners or use clearinghouses that guarantee payment but charge fees. Swaps also require ongoing monitoring. Market movements, regulatory changes, or shifts in economic conditions can affect the value of a swap over time, meaning companies must continually assess their positions.

Despite these risks, swaps remain a core component of modern finance. Banks, corporations, insurance firms, investment funds, and governments use swaps every day to control financial exposure, stabilize operations, and plan for the long term. Their flexibility and efficiency make them particularly valuable in a world where interest rates, currency values, and commodity prices are constantly changing.

In simple terms, a swap is like a financial agreement that allows two parties to reshape their cash flow obligations without altering the underlying assets. Whether used to hedge risk, take advantage of market trends, or gain exposure to specific assets, swaps help create stability in an otherwise unpredictable environment. Understanding how swaps work—and the opportunities and risks they carry—gives businesses and investors powerful tools to navigate global markets with more confidence and clarity.